Iceland, spelled in Icelandic, is Island, the plain English word “island.” But when Icelanders pronounce their country’s name, Island, it sounds different, Eesland, instead of island. “Island” spells “Island” means Iceland, my mother’s first home. As a child learning to love words, I ponder this oddity and the unpredictable nature of that far-away and mysterious place. Iceland is the land of fire and ice. It can explode like my mother does sometimes, in white-hot rage. And it has cold dark winters as bleak as my mother’s face on a November morning when she can’t get out of bed, when the effort of making breakfast for us before we go to school is too much.

It is the 1970s, and I am maybe seven. I watch a color tv documentary with my mother about the emergence—through four years of volcanic eruptions–of a new island, named Surtsey, off the southwest coast of Iceland. My mother was born and raised in village of Isafjordur that rests in the crook of a northern fjord. In her thirties, she moved to the US with my American dad and their combined family of five. I am her seventh child, one of two girls born to her after she became a foreigner, living just outside America’s capital city.

Usually when she watches tv, my mother’s hands are busy with knitting or needlepoint, her eyes glancing up at the screen as she works. But now, sitting in the basement of our five-bedroom house that she keeps “spic and span,” Mamma’s attention is rivetted, her chin resting on her palms as she leans toward the image of a hot ash explosion lifting over ocean water. This is unbelievable! She exclaims. There was nothing there, and now there is an island. A cooling gray river of lava, red underneath, flows slowly into the water and hardens with a crackling hiss, meeting the North Sea like a sworn enemy.

Under the water, subterranean vents continue to discharge magma that piles on top of itself in layers until it expands the land mass named for Sutr, a Norse fire giant. Surtsey began to form in 1963, and grew into a rounded mile of land where once there was only moving water. It is a slowly greening island, now eroded to half its original size. Surtsey holds a solitary place above the ocean; its only part-time residents are sea birds, seals, and scientists.

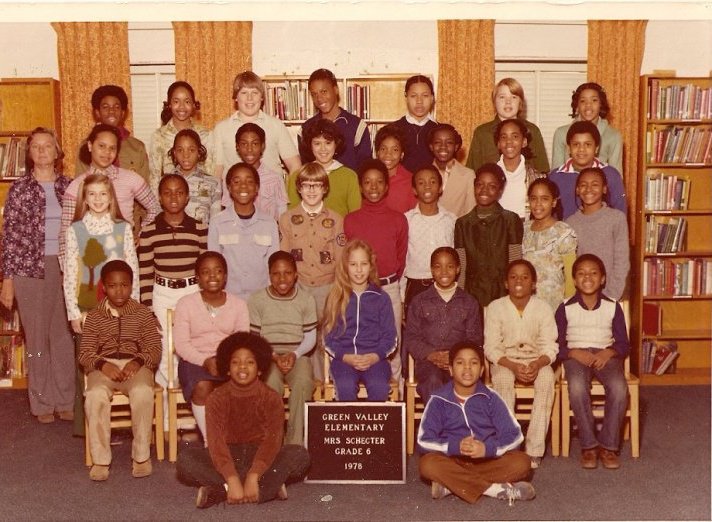

In fifth grade, in Mrs. Corkum’s class at Green Valley Elementary, each of us draws our own map of the world. Standing in her blue skirt, brown hair pulled back into a bun, our teacher holds a globe in her hands. I locate Iceland by looking for the white-painted oblong of Greenland at the top of the Atlantic, then finding the rough-edged island tucked below to its right, just outside of the arctic circle. The class is paying attention because we all like Mrs. Corkum–she is fair and talks to us like we are smart, almost grown-up. Class, when we draw our maps, continents that are small will look bigger, and some things that are big will look smaller. We are flattening something that is curved to fit it on our paper. The round world, represented flatly, is distorted. This feels true to me.

I pencil faint guide-lines, holding my hand next to a wooden ruler with a thin, metal edge bent at one corner. My map is bisected vertically by the Prime Meridian, which is intersected by the Equator, and by the Tropics of Cancer and Capricorn. We draw Madagascar first, a fat ell-shape off the right-hand coast of Africa. I trace precise coastal shapes set within the grid of latitude and longitude. Starting with Madagascar, then working our way around the world, my class copies the world map one shape at a time. Tracing coastlines through meridian grids, pencil gripped too tightly, I recreate the world in the shape of islands.

Americans don’t even know where Iceland is! my mother complains. But I do. I know Iceland is a small, independent country that had democracy hundreds of years before America got its start. And I know about Leif Erikson–Mamma teaches me to say his name right, so it sounds like “Laif,” not like “leaf”. He was the first European to go to North America, in a sturdy Viking ship. Iceland is part of Scandinavia and also part of Europe. In Iceland, women know how to dress. They don’t go around to the stores in blue jeans, and they don’t have to be skinny or stupid to be pretty. Icelandic women are not like American women. They are one right way. Like me at ten, they know that they know a lot.

Iceland happens apart from me as I watch my mother’s back. She turns herself to the endless routine of cooking and cleaning, grocery shopping and cigarette smoking. She scrubs and she shines, always moving. A few months later, she seems to just sink into herself, the fiery island pummeled by scouring waves.

As I grow up, my mother’s language is like the water surrounding Iceland, chilling in its depth. Icelandic mystifies me, pulls my full attention to its musical cadence of words I don’t speak or understand. I see the surface of the language; images appear in my head when one of the few words I know float by. I can say “sael” for hello with a proper back-of-the-tongue click on the ell, and I say “bless” for goodbye, the polite beginning and ending. “Jaejae” is an all-purpose word of mild impatience that winds things up. Jaejae, says my mother as she inhales and stands up from the kitchen table, where a yellow ashtray rests half-full. I know she is getting ready to hang up the phone after talking to one of her Icelandic friends who also lives not far from us. The landline phone is anchored high to the wall, in the doorway to the dining room. It has a twisted cord long enough that Mamma can get up and look out the back door, toward the north, as she talks in her private language.

Every land form surrounded by water is a version of my mother’s home. I sit with the tip of my tongue drying in the air, tracing the shape of Madagascar. It is bigger than Iceland. It is warmer than Iceland. It is far away from Iceland. Iceland. Island. Eesland. The place I go in my mind where the air is always clear, where my mother is happy because she is in her real home. My Iceland is both far-away and more real than this America where childhood plods along, where I make the dreary winter walk to school while dreaming of riding a sure-footed Icelandic pony past moss-covered fields of ancient lava rocks.

But I am not there. I am not even all the way in America. I can’t be popular or all the way American or brash like a boy, so in fifth grade, I try to copy the world onto paper and make it look good, make it right. Over weeks, all of the continents appear, and finally, I add the dragon shape of Iceland. Sitting up in my wooden chair and setting my blue pencil down, I see a miniscule piece of the gigantic world, almost meaningless next to so many other place shapes. Surtsey is so tiny that even adding it as a dot would be wrong.

Our world maps are drawn on three separate sheets of paper that cover the surface of our small desks. After weeks of work, with new calluses on our index fingers, we carefully connect our pieces of flattened earth using invisible tape. My map looks how I want it to look, just right, pleasing to Mrs. Corkum and to me. It is hung in the school hallway alongside the worlds of my classmates, and every time I walk by, my eye goes straight to Iceland, confirming its existence. Even today, I can’t help but center the world and much of my imagination exactly there.