When my boys were young, we read K.A. Applegate’s Animorphs series, about alien worms who crawled into people’s ears in order to take over their brains. These interstellar slugs were slowly conquering the world. At regular intervals, the alien worms, called yeerks, returned to their collective pool to regenerate. Human hosts, controlled by the aliens, would lean down at the edge of the goopy water as the slugs oozed out to do their yeerk thing and strategize about how best to control the universe, one slugged brain slug at a time. Luckily, a group of intrepid young humans had gained the ability (from good aliens, of course) to morph into animals. So, as soaring hawks or hive-brained ants, they waged covert battle with the yeerks.

When my son, now thirty, has bipolar depression, as he does today–immobilized by invisible neurostorms–I think of the Animorphs shouting to each other, as they prepare for yet another impossible mission, Time to kick yeerk butt! And off they go to save the world.

When I meet someone who might become a friend, I often take the risk of disclosing that my son carries a bipolar diagnosis. Then I brace myself for the harshness of the typical first question: Is he taking meds? Or recently: Is he taking drugs? “Drugs?”–that one stumped me. Were they asking if he also has addiction, as so many folks with bipolar do, or were they blending the term for prescribed medications and street drugs? In these conversations, I often hear about someone’s sibling, ex-partner, or parent who struggled with mental illness. But the medication question almost always comes first. As if medications are a fix, as if surrendering the brain to psychiatry makes bipolarity disappear.

The “take medication, be fixed” way of thinking is familiar. I thought that way myself a dozen years ago, when my son was an intellectually gifted teen with a rebellious streak. Before his first real manic episode bloomed like toxic algae, before our family’s genetic pattern was revealed. Before I visited my elderly mother in the psychiatric ward, and before two of her other grandchildren were also diagnosed. For so long, I didn’t know I was thinking, why don’t people just take their medications? But I was.

Every year that goes by, I am more and more grateful for the miracle of modern psychiatric medications, for the lives they improve and the lives they save. And still, more than once, more than twice, my son has been following every recommendation of a complex treatment plan—medication combinations, support groups, highly skilled on-going psychotherapy—and boom, he is hit, as if by a stray bullet. Up he goes like a shining, untethered balloon. Or down he goes into the dark pit of depression. These cycles leave him facing yet more lost opportunities, yet more go-rounds of self-blame. The yeerks are at it again.

How to be a mother on days like this? I want to morph into a bull elephant and drain the pond where the alien yeerks strengthen, where they strategize ways to rob humans of their freedom and self-command. I try instead to stick to my known super-powers, encouragement and food. Every day, I tell him I love him and ask if he’s eaten his vegetables. I text him funny memes, even when I know his phone is off. I buy organic spinach and kale, heaping it onto his plate at every opportunity. Of course, no amount of mother love can banish symptoms. I beat back my grief and helplessness. I battle my destructive impulse to make everything right by sheer force of will. Then, slowly sink into the hard-won understanding about my mother, my son, myself: all of us, always, are doing our best. Yes, it helps to take medication, and no, even the bravest heroes are not always cured. But on they go, day by day, season by season, kicking yeerk butt.

This continent that birthed the human race so long ago is now home to my niece, Rachel, who works as a researcher for one of the many non-governmental organizations in Lilongwe, Malawi. When she arrived to pick me up at the airport, I greeted her in Chichewa: Moni. Muli Bwanji? I have practiced the simple Hello, how are you? many times on the plane, but these short phrases don’t stay in my travel-soaked brain for long.

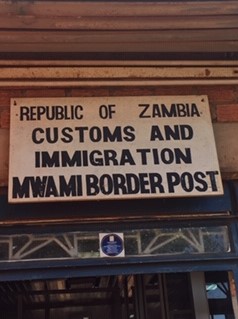

This continent that birthed the human race so long ago is now home to my niece, Rachel, who works as a researcher for one of the many non-governmental organizations in Lilongwe, Malawi. When she arrived to pick me up at the airport, I greeted her in Chichewa: Moni. Muli Bwanji? I have practiced the simple Hello, how are you? many times on the plane, but these short phrases don’t stay in my travel-soaked brain for long. closely related Nyanja dialect. My polyglot niece doesn’t get to practice her French, Spanish, or Russian very often while living and working in Africa. I, however, thanked a Zambian immigration officer by saying Gracias, and I greeted Rachel in the morning as I do my sons at home, in my mother’s Icelandic: Godan daginn allan daginn. It means “good morning, all day,” but Rachel gave me a quizzical look in response.

closely related Nyanja dialect. My polyglot niece doesn’t get to practice her French, Spanish, or Russian very often while living and working in Africa. I, however, thanked a Zambian immigration officer by saying Gracias, and I greeted Rachel in the morning as I do my sons at home, in my mother’s Icelandic: Godan daginn allan daginn. It means “good morning, all day,” but Rachel gave me a quizzical look in response. quick breath to peek at the world and then swim-doze the day away. Mesmerized by the adorable ear-flapping, I can’t look away. My laptop goes into sleep mode. At this point in the trip, I am the dependent one, following my niece around like a baby duck to mooch off of her WiFi hot spot and translation skills. Rachel makes me coffee and cooks me oatmeal before she opens her computer and starts running data sets for her project–actually working–as I gaze at the fast-flowing river.

quick breath to peek at the world and then swim-doze the day away. Mesmerized by the adorable ear-flapping, I can’t look away. My laptop goes into sleep mode. At this point in the trip, I am the dependent one, following my niece around like a baby duck to mooch off of her WiFi hot spot and translation skills. Rachel makes me coffee and cooks me oatmeal before she opens her computer and starts running data sets for her project–actually working–as I gaze at the fast-flowing river. flags, first the mother, then the imitating baby waving their ears in synchronized tempo before ambling away to snack a different set of shrubs. I surprise myself by wanting to cry. The elephants are so wild and intelligent, so distinctly and fiercely familial.

flags, first the mother, then the imitating baby waving their ears in synchronized tempo before ambling away to snack a different set of shrubs. I surprise myself by wanting to cry. The elephants are so wild and intelligent, so distinctly and fiercely familial.

counts out M&M’s for me and my sister. We get fifteen each, in small metal cups meant to hold soft boiled eggs. I have polished Daddy’s black shoes until they shine. They sit on a section of newspaper by the kitchen door, waiting. Save your M&M’s, Mamma says, before our parents drive off into the evening. Make them last a long time!

counts out M&M’s for me and my sister. We get fifteen each, in small metal cups meant to hold soft boiled eggs. I have polished Daddy’s black shoes until they shine. They sit on a section of newspaper by the kitchen door, waiting. Save your M&M’s, Mamma says, before our parents drive off into the evening. Make them last a long time! After the local news, Rod Sterling’s voice describes the time I dread: The Twilight Zone. I am sleepy, but I won’t go into our room alone, so I put a pillow over my head and drift off. I don’t wake up when my father carries me to my bed.

After the local news, Rod Sterling’s voice describes the time I dread: The Twilight Zone. I am sleepy, but I won’t go into our room alone, so I put a pillow over my head and drift off. I don’t wake up when my father carries me to my bed.